Combined Chemotherapy: Maximizing Treatment Effectiveness for Cancer Patients

– Combination chemotherapy is the use of more than one medication at a time to treat cancer.

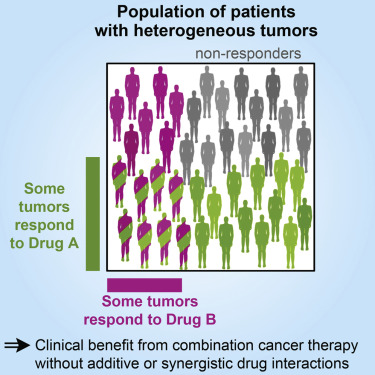

– Using a combination of drugs increases the chance of eliminating all cancer cells, but it also increases the risk of drug interactions.

– Combination chemotherapy was inspired by the approach to treating tuberculosis using a combination of antibiotics.

– Combination chemotherapy has been found to be more effective for treating certain cancers such as acute lymphocytic leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

– Combination chemotherapy is more effective than single drug therapy and sequential chemotherapy.

– Targeted therapies, which block specific pathways in cancer cells, have been used in combination with chemotherapy.

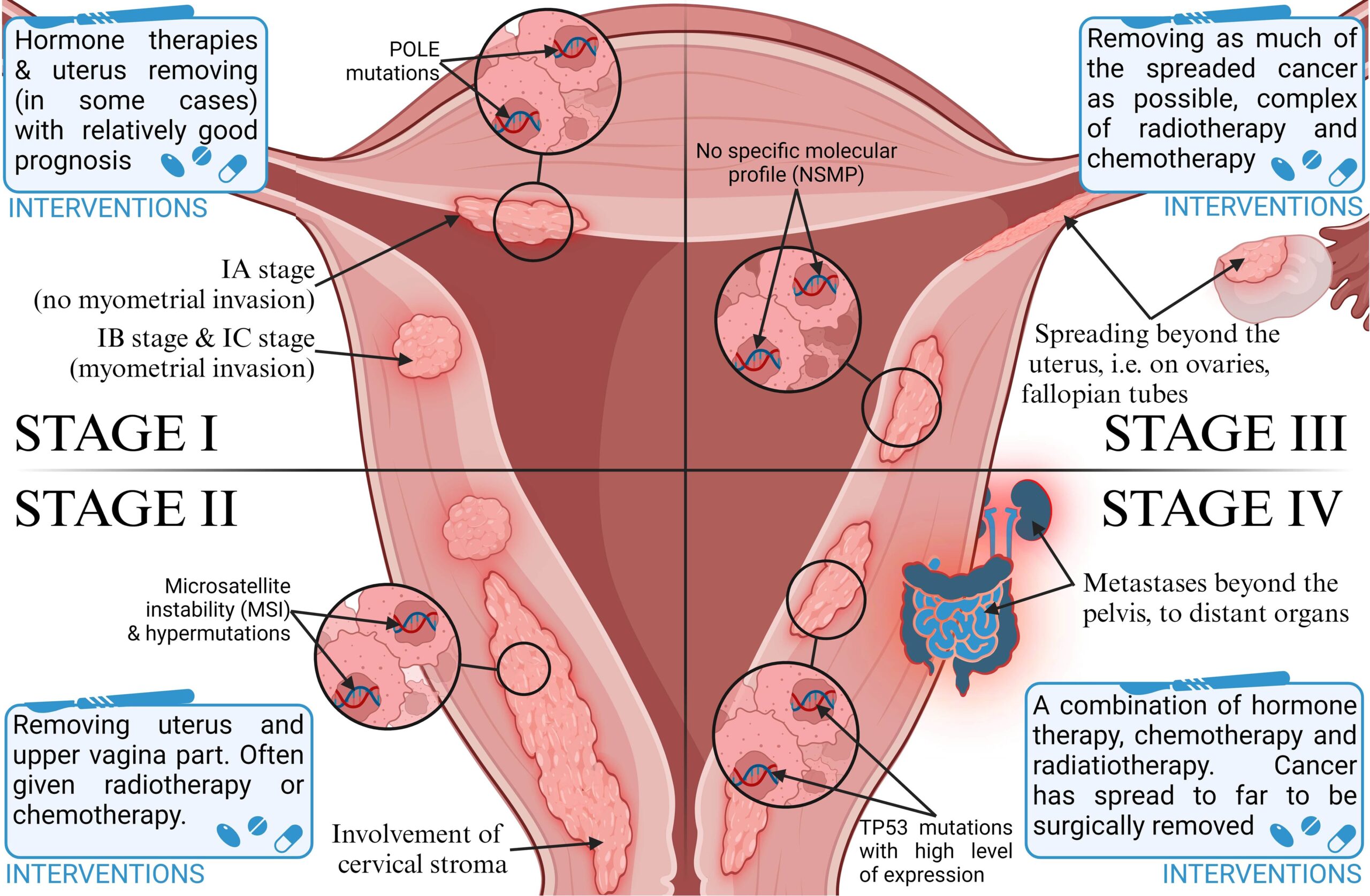

– Combination chemotherapy is used for various types of solid tumors, such as non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer.

– Combination chemotherapy is also used for certain leukemias and Hodgkin lymphoma.

– Chemotherapy used in combination with immunotherapy can enhance the effectiveness of both treatments.

– Immunotherapy drugs help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

– The abscopal effect, where chemotherapy helps the immune system target abnormal cells, can occur when chemotherapy is combined with immunotherapy.

– Combination chemotherapy has increased survival rates for many diseases.

– Combination chemotherapy involves using multiple chemotherapy medications at the same time.

– There are several advantages to using combination chemotherapy, including decreased resistance of tumors to treatment, earlier administration of medications, targeting multiple processes in cancer growth, increased effectiveness, lower doses of medications, and synergetic effects of drug combinations.

– Combination chemotherapy has been found to improve survival or result in a better response to treatment, especially as adjuvant treatment after surgery.

– However, there are also disadvantages to combination chemotherapy, including an increased risk of side effects.

– The article discusses the use of multiple chemotherapy drugs in combination treatment.

– It states that when multiple drugs are used, side effects of both drugs may compound.

– For example, if two drugs that cause a low white blood cell count are used, the risk of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is increased.

– If a person develops a side effect while taking multiple medications, it may be difficult to determine which medication is responsible.

– In these cases, all medications may need to be discontinued if the side effect is serious.

– Sometimes side effects occur due to interactions between medications, not because of a specific medication.

– The more medications a person is taking, the greater the chance of an interaction occurring.

– Combination chemotherapy can extend life, reduce the risk of cancer recurrence, and improve the results of immunotherapy.

– However, adding more medications can increase side effects and the intensity of treatment.

– Advances in managing side effects have been made, such as anti-nausea drugs reducing or eliminating nausea, and drugs increasing white blood cell count allowing for higher and more effective doses of chemotherapy.