– Face presentation is a cephalic presentation in which the head is completely extended.

– The incidence of face presentation is about 1 in 300 labours.

– Primary face presentation occurs during pregnancy and may be caused by factors such as anencephaly, loops of the cord around the neck, foetal neck tumors, hypertonicity of neck muscles, dolicocephaly (long antero-posterior diameter of the head), dead or premature foetus, or idiopathic causes.

– Secondary face presentation occurs during labour and may be due to factors such as contracted pelvis, pendulous abdomen, marked lateral obliquity of the uterus, further deflexion of brow or occipito-posterior positions, or other malpresentations such as polyhydramnios and placenta praevia.

– Left mento-anterior (LMA) and right mento-anterior (RMA) are more common positions of face presentation.

– Diagnosis during pregnancy is difficult, but the back is difficult to feel and the limbs may be felt more prominently in mento-anterior position. Ultrasound or X-ray can confirm the diagnosis.

– Diagnosis during labour is done through vaginal examination, which shows identifying features such as supra-orbital ridges, malar processes, nose, mouth, and chin.

– Late in labour, the face may become oedematous (tumefaction), which can be misdiagnosed as a buttock (breech presentation). Differentiating factors include the formation of a triangle with foetal mouth and malar processes as apexes, anus on the same line as ischial tuberosities, feeling of a hard gum through the mouth, and no hard object through the anus.

– The mechanism of labour in mento-anterior position involves descent.

– Engagement by submento-bregmatic diameter: 9.5 cm

– Submental region hinges below the symphysis in flexion position

– Submento-vertical diameter: 11.5 cm

– Biparietal diameter does not pass the plane of pelvic inlet until the chin is below the level of the ischial spines and the face begins to distend the perineum

– In about 2/3 of cases, long anterior rotation of 3/8 circle occurs during mento-posterior position

– In about 1/3 of cases, deep transverse arrest of the face, persistent mento-posterior, or direct mento-posterior occur during mento-posterior position

– Direct mento-posterior cannot be delivered due to obstruction caused by the length of the sacrum and neck

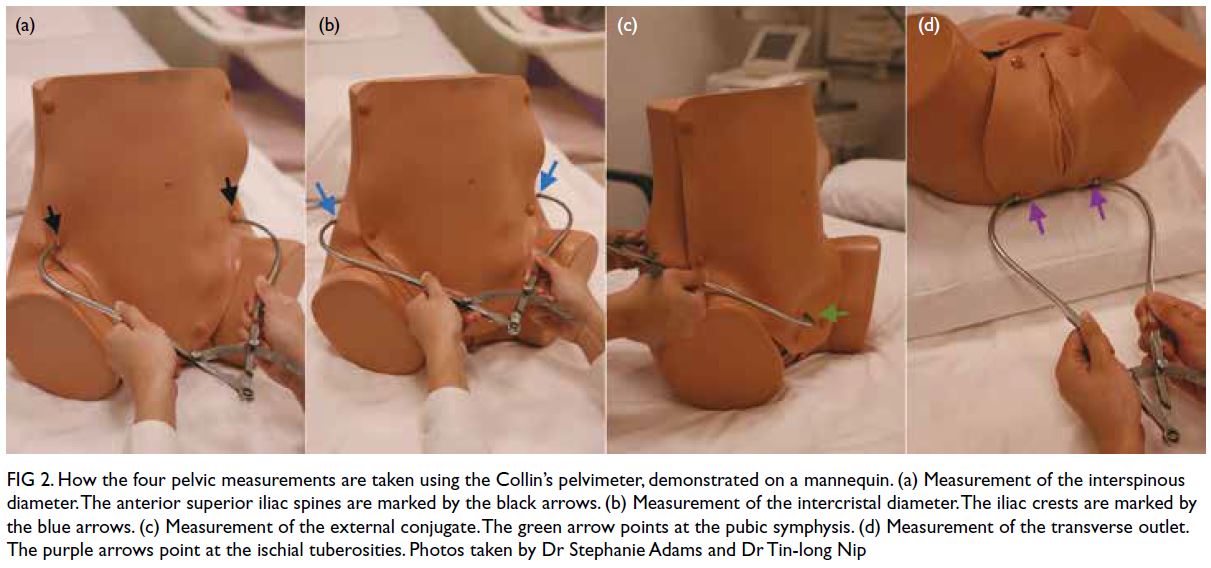

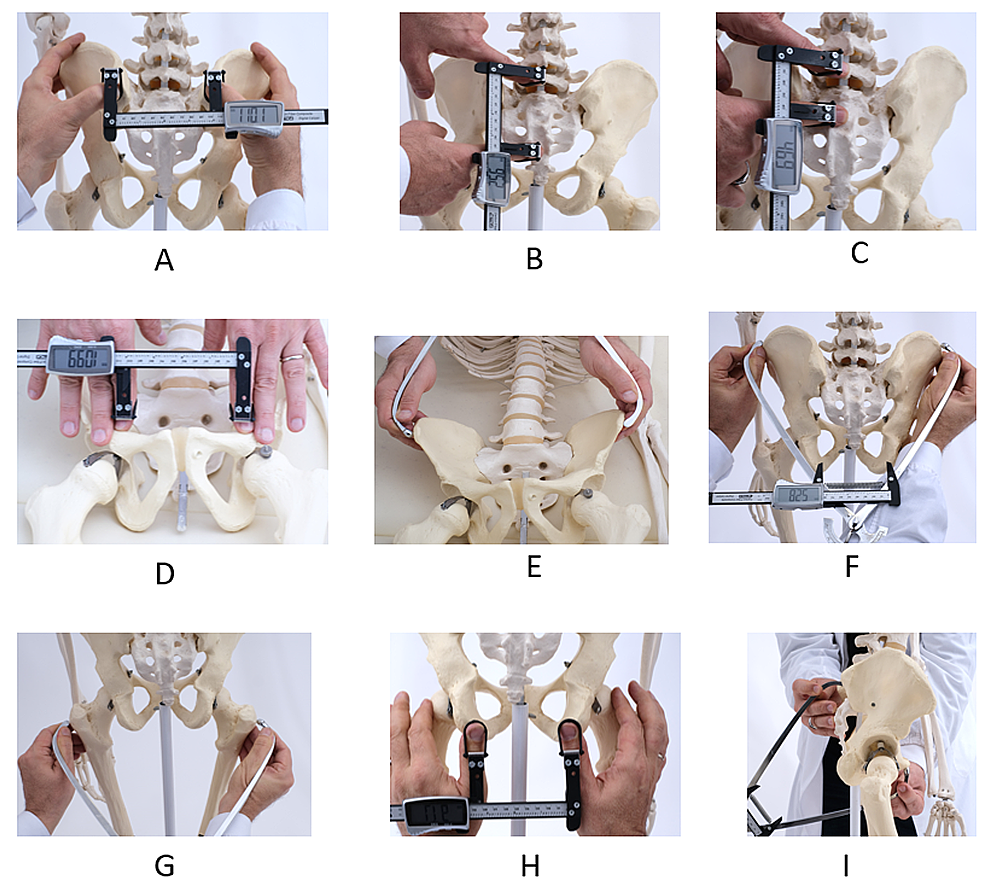

– Management of labour includes excluding foetal anomalies and contracted pelvis

– Spontaneous delivery usually occurs in mento-anterior position during second stage of labour

– Forceps delivery and episiotomy may be indicated in prolonged second stage of labour in mento-anterior position

– Wait for long anterior rotation of 3/8 circle in mento-posterior position during second stage of labour

– Oxytocin is used to compete inertia during this period if there are no contraindications

– Caesarean section is the safest option if long anterior rotation fails or there is foetal or maternal distress

– Manual rotation and forceps extraction or rotation and extraction by Kielland forceps are alternative methods, but are hazardous and not commonly used

– Craniotomy may be performed if the foetus is dead

– Complications may occur, refer to complications of malpresentations and malposition for more information.

– There is an increased risk of trauma to the baby in face presentation, so internal manipulation, vacuum extractors, and manual extraction should be avoided.

– Abnormalities in fetal heart rate are more common in face presentation. Monitoring is crucial during labor.

– Complications of face presentation include prolonged labor, facial trauma, facial edema, skull molding, respiratory distress, spinal cord injury, abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, and low Apgar scores.

– Informed consent should be obtained from the mother, and failure to do so is considered negligence.

– Forceps and oxytocin used during labor can put a baby at risk of complications. Forceps can cause head injuries and oxytocin can deprive the baby of oxygen due to strong contractions.

– Mothers should be given the option of a C-section if facing complications.

– Face presentation babies should be closely monitored and delivered by an experienced physician.

– If negligent practices cause injury to the baby, it can be considered medical malpractice. ABC Law Centers specialize in birth injury cases and offer free legal consultations.

Continue Reading