– Prognosis for theca cell tumors (GCTs) is generally very favorable and considered to be tumors of low malignant potential

– Approximately 90% of GCTs are at stage I at the time of diagnosis

– 10-year survival rate for stage I tumors in adults is 90-96%

– GCTs of more advanced stages have 5- and 10-year survival rates of 33-44%

– Overall 5-year survival rates for patients with adult-type GCTs (AGCTs) or juvenile-type GCTs (JGCTs) are 90% and 95-97% respectively

– 10-year survival rate for AGCTs is approximately 76%

– Recurrence rate for AGCTs is 43%

– Average recurrence for AGCTs is approximately 5 years after treatment, with more than half occurring more than 5 years after primary treatment

– Mean survival after recurrence is diagnosed is 5 years for AGCTs

– 10-year overall survival after AGCT recurrence is 50-60%

– JGCTs tend to recur much sooner, with more than 90% of recurrences occurring in the first 2 years

– Tumor stage at initial surgery is the most important prognostic variable

– Other factors predicting survival include early stage disease, age younger than 50 years, high mitotic rates, moderate-to-severe atypia, preoperative spontaneous rupture of the capsule, and tumors larger than 15 cm

– True thecomas have a 5-year survival rate of nearly 100%, but may cause increased morbidity due to estrogen-producing capabilities

– More than 90% of AGCTs and JGCTs are diagnosed before spread occurs outside the ovary

– Five-year survival rates for stage I tumors are usually 90-95%

– AGCTs have a 5-year survival rate of 25-50% for patients with advanced-stage disease

– Late recurrence can occur up to 37 years after diagnosis

– Approximately 20% of GCT patients die from the disease in their lifetime

– Morbidity is primarily due to endocrine manifestations of the tumor

– Physical changes caused by high estrogen levels usually regress after tumor removal, but some patients may present with symptoms of androgen excess

– Estrogen production can stimulate the endometrium, leading to endometrial hyperplasia in 30-50% of patients and endometrial adenocarcinoma in 8-33% of patients

– There may also be an increased risk of breast cancer, although it’s difficult to prove a direct correlation

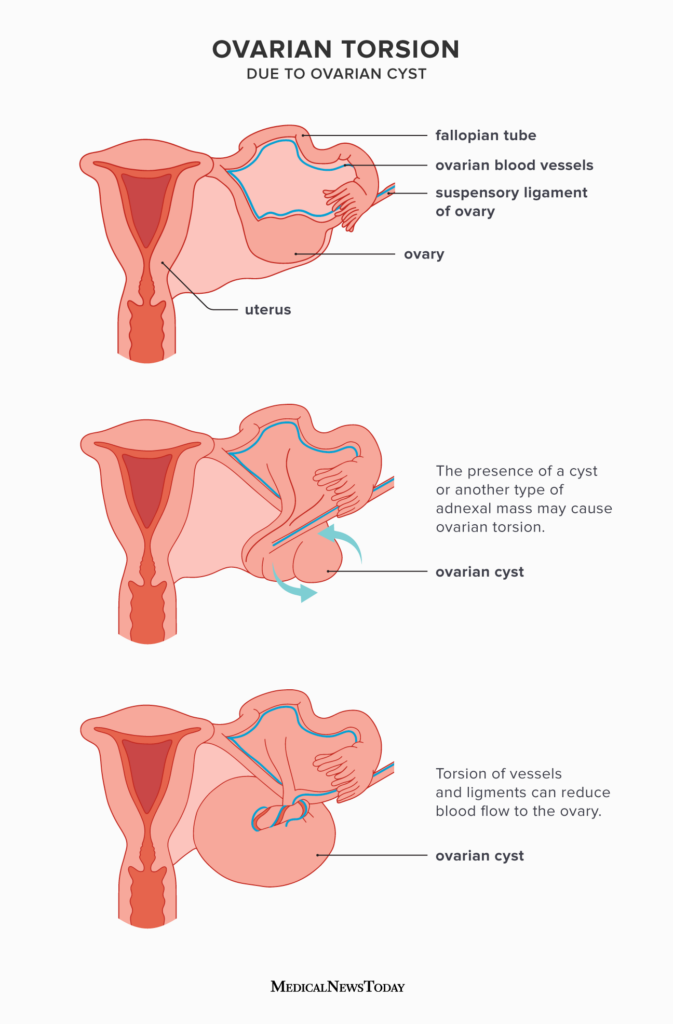

– Acute abdominal symptoms can occur in 10-15% of cases due to rupture, hemorrhage, or ovarian torsion

– Adverse effects from chemotherapy vary depending on the type given

– The standard of care for initial management of GCTs is surgical

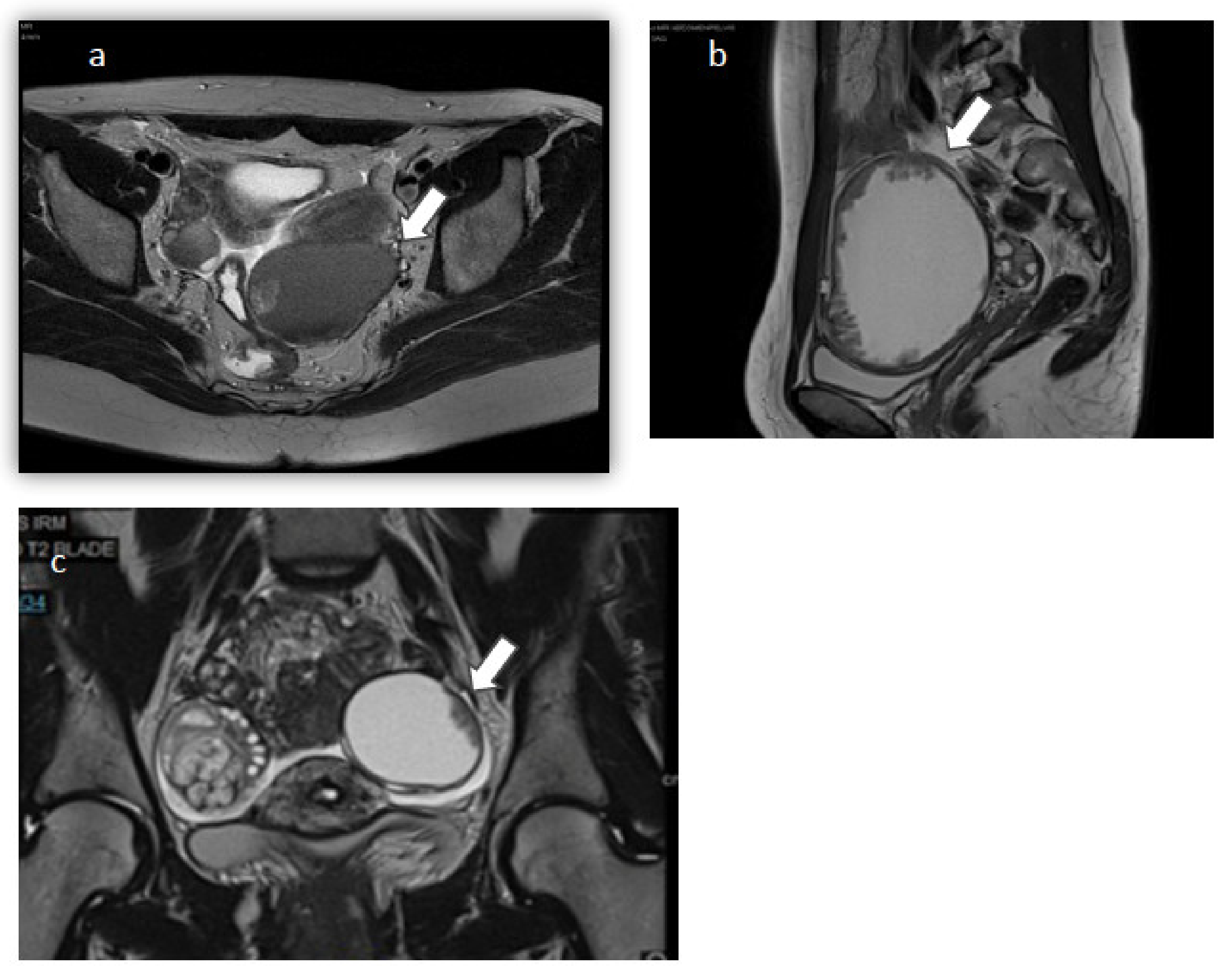

– Preoperative evaluation, including imaging and laboratory studies, helps measure the extent of the disease

– Complete surgical staging is important and involves examination of the pelvic and intra-abdominal structures

– Optimal tumor debulking improves overall survival and decreases recurrences

– In younger patients who desire future fertility, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is usually sufficient treatment

– Staging typically involves pelvic washings, lymph node sampling, biopsies, and examination of the contralateral ovary

– The need for lymphadenectomy is being questioned due to the low risk of lymph node metastasis even in advanced stage disease

– Dilatation and curettage should be considered to rule out a neoplastic process of the endometrium in younger patients

– Surgical staging/biopsy based on incidence of microscopic extraovarian disease is important

– For patients who do not require future fertility, surgical therapy should consist of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy, in addition to staging procedures

– The treatment of recurrent GCTs is not standardized, and surgical debulking may be beneficial if the tumor appears to be focal on imaging studies

– Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormonal treatments have been used with varying success

– The mean survival after a recurrence has been diagnosed is approximately 5 years for adult GCTs.

Continue Reading